We all know that the New Zealand roads need fixing, and we need new infrastructure. But where is the money going to come from?

We need a real focus on the source of funding and the assurance that the money will be well spent. At the moment we have no confidence that those who need to be working on solving this, are.

We want value for money and greater certainty in pricing. Government and its agencies need to be much more transparent on value for money and outcome-focussed. The spend may be increasing but in terms of road maintenance is that getting more resealing done, or more rehab done, and is the life of the road meeting expectations?

On capital projects, these numbers show pricing is simply a joke:

Transmission Gully

In December 2009, Minister of Transport Steven Joyce announced the government’s commitment to the new SH1 project in Wellington as one of seven Roads of National Significance, with a predicted project cost of $1.025 billion.

In October 2013, Prime Minister John Key said he expected the 27km project to be ready by 2020 and to cost $2.5 billion.

In February 2020, it was announced that the expected cost of $850 million had ballooned by another $191 million. In March 2021, the road was projected to cost $1.25 billion by its then-expected opening date in September 2021.

Transmission Gully finally opened in March 2022 but the total cost was unclear, according to the NZ Herald. The opening ceremony alone cost taxpayers $336,712.

The construction cost worked out as $46.3 million per km, but only assuming a $1.25 billion cost.

Te Ara Tepua walking and cycle way in the Hutt Valley

In 2019, Waka Kotahi predicted it to cost up to $94 million. In April last year, that sum had risen to $190 million.

The construction cost: $69.3 million per km ($312 million for 4.5km).

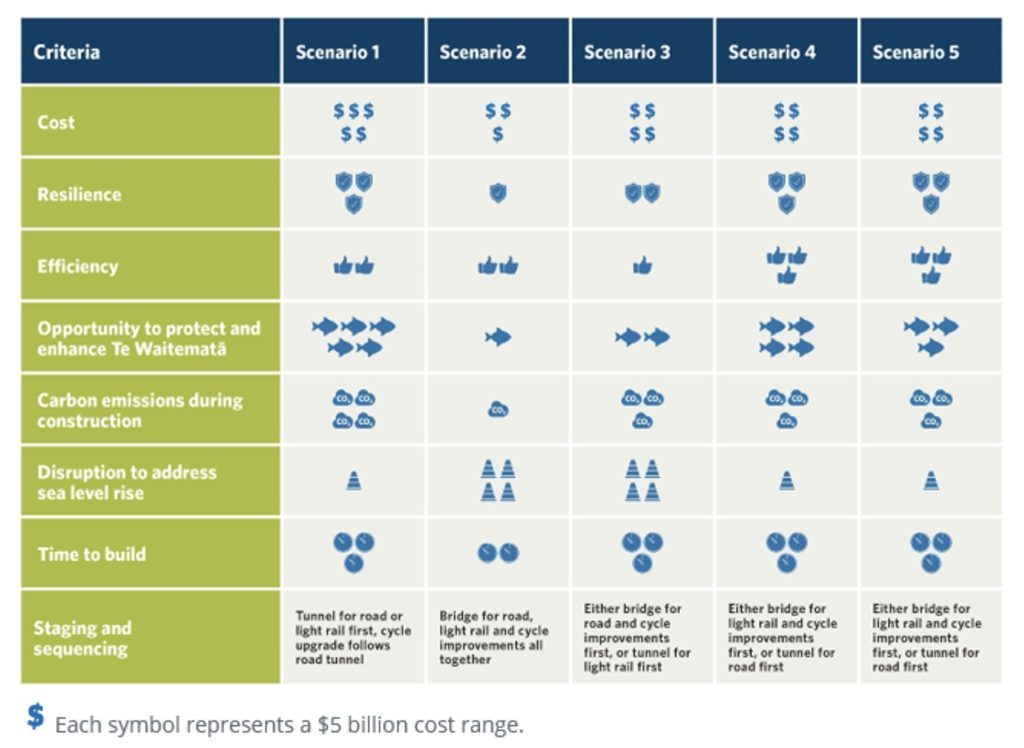

Waitemata Harbour Crossing (alternatives to the 1km Auckland Harbour Bridge)

The consultation document, prepared by Waka Kotahi, listed one scenario costing $15 billion; three scenarios at $20 billion; and one scenario at $25 billion. (See graphic below.)

At a time when many households are struggling to find ways to cut the weekly budget because of the cost-of-living crisis, one might be forgiven for questioning whether government agencies have the same stringent approach. What’s a few hundred million dollars or even a few billion dollars between friends?

Granted, New Zealand is a small country and we simply haven’t got enough money for everything, so that begs the question where could it come from. It has to come from somewhere. Should it be road user charges (RUC)? Fuel excise tax (FED)? The National Land Transport Fund (NLTF)? General taxation? Tolls? Overseas investment?

There’s no question, we want NLTP ring-fenced for roads. Taking money out of it for rail and coastal shipping is not on, especially now there is a rail tax for infrastructure. Pressure to introduce inefficient tolls on roading improvements are a natural result.

Tolling is also not a silver bullet. Transporting New Zealand opposed the Penlink Road Tolling scheme, in Auckland. It was difficult to see any justification for implementing a toll on a relatively short piece of roading infrastructure. The $120 million collection cost that the Ministry of Transport predicts to bring in $5 million a year in tolls also seems a poor investment. It’s concerning to see that the Minister of Transport proceeded with tolling, despite his ministry advising that the evidence provided by Waka Kotahi was weak.

There is significant public good in a well-maintained roading network, both to move people and freight reliably, and to ensure this movement is safe.

The disconnections and perplexing prioritisation in government transport policymaking is both frustrating and challenging. Our members simply wouldn’t survive if they operated their businesses with so little certainty or accountability on their pricing and levels of service so we’re calling on government and its agencies to pick up their game.